Building social connections

The idea of loneliness often suggests a lack of human contact. Stock imagery depicts loneliness with pictures of forlorn individuals sitting on their own. Go-to literary references for the lonely include Boo Radley and Quasimodo – recluses painfully isolated from their peers.

Of course physical solitude can prompt feelings of loneliness, but it can also be a peaceful experience under the right circumstances. On the other hand, being part of a crowd and failing to connect with the people in it is a universally disheartening experience. According to a seminal sourcebook on the topic, the soundest way to describe loneliness is “a discrepancy between one’s necessary and achieved levels of social interaction.” Indeed, it’s human kinship, rather than simple proximity, that satisfies people’s emotional needs. To put it another way, physical togetherness is not the same as emotional togetherness.

“It’s kinship, rather than proximity, that satisfies people’s emotional needs.”

In her 2016 book The Lonely City, Olivia Laing writes of the “particular flavour to the loneliness that comes from living in a city, surrounded by millions of people. One might think this state was antithetical to urban living... It’s possible – easy, even – to feel desolate and unfrequented in oneself while living cheek by jowl with others.” More than half of the world’s citizens already live in cities, and the United Nations predicts this will grow to two-thirds by 2050. It’s crucial that we reckon with the confluence of urban factors – from poor connectivity to high costs of living – that erode opportunities for social cohesion and put city dwellers at particular risk of loneliness.

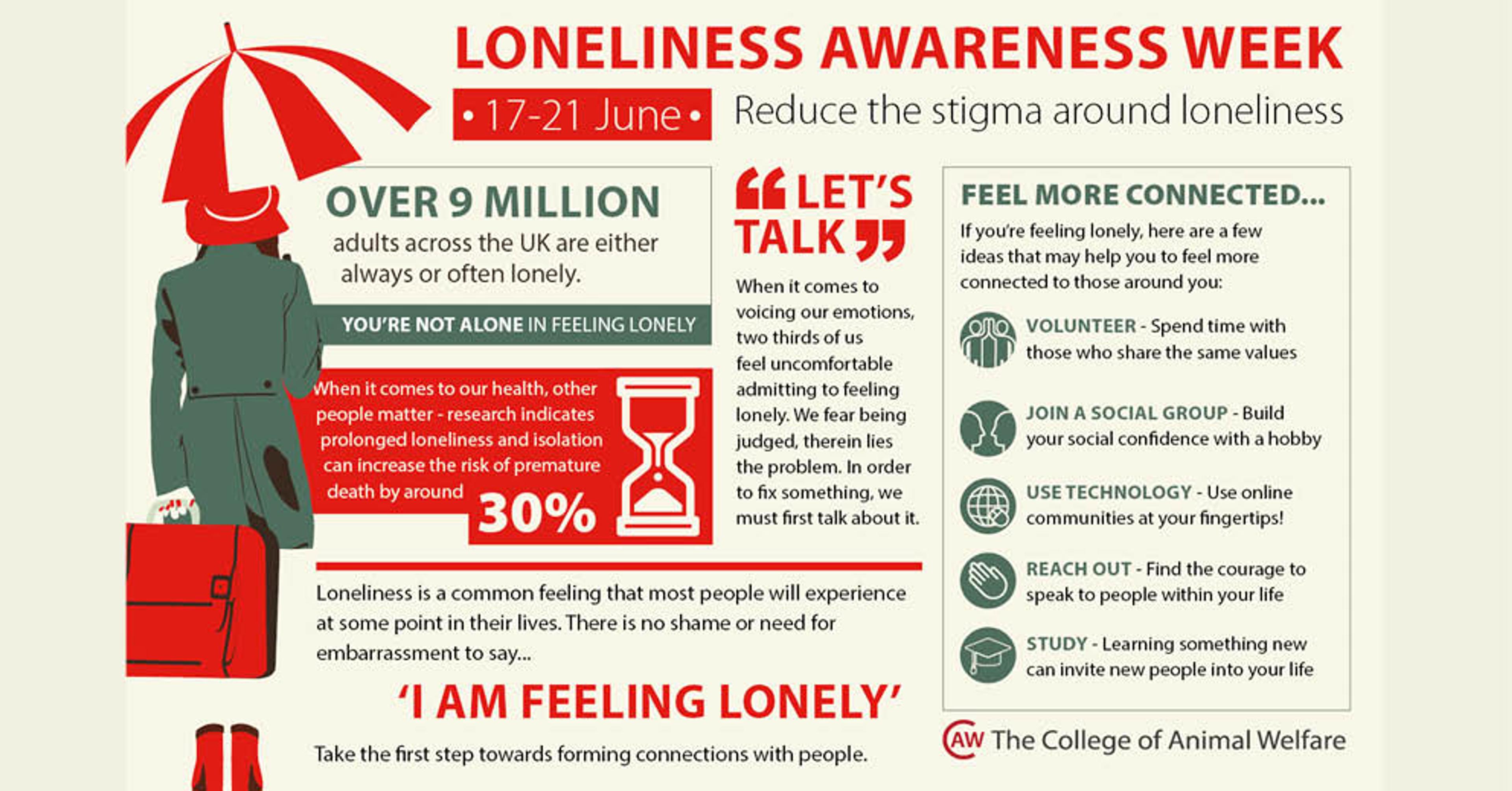

There’s some debate as to whether loneliness is a growing problem percentage-wise or, as the global population increases, simply a more visible one. There’s no question that it’s become more prevalent as a topic of social concern, particularly as its health consequences become apparent, including the stark statistic that loneliness can increase someone’s risk of premature death by 30%.

Around the world, campaigns, networks and helplines have sprung up to call attention to such consequences. The Australian Coalition to End Loneliness has drawn together research from a variety of universities and agencies to address the physical, psychological, social and economic costs of loneliness in Australia. Over in the USA, bodies like Cigna and the AARP have conducted large-scale surveys measuring subjective feelings of loneliness in American adults, while the University of Hong Kong recently used its Say No to Loneliness project to propose strategies for strengthening intergenerational support and communication among the country’s elderly.

Meanwhile in the UK, the cross-disciplinary Campaign to End Loneliness has released formal guidance for local authorities and commissioners to address the issue in older demographics, and dozens of organisations have participated in the Loneliness Lab, devised to combat social isolation among Londoners. The UK government even named an official Loneliness Minister in 2017. Mims Davies, the most recent postholder, kicked off the newly established Loneliness Awareness Week in 2019 with the help of major British charities and businesses.

Panellist Alex Smith jumped in to suggest “togetherness” as the most precise counter to loneliness – not simply engaging with other people but feeling socially connected to them in a way that offers a sense of purpose and belonging. Alex is the founder of The Cares Family, a charity that matches young professionals with older neighbours to encourage intergenerational friendships. He noted the rise of technology and convenience culture and the way these deter natural interaction in public spheres.

“On the way here I bought a coffee from a machine. I had my massive new headphones on, which are soundproofing. I didn’t speak to the bus driver, didn’t speak to anybody on the Tube. And when I was on the Tube, nobody looked at me. We, in our political economy, have prioritised what’s efficient over what’s important. We’re more interested in what saves time – technology and those sorts of things – than the way we spend time, right? And I mean spending time not just with people you know and are already familiar with, but people who are not like you as well.”

As the conversation progressed, the panel’s attention turned to the varying scales on which loneliness manifests in people’s daily lives. Andrew Stevenson, a doctor of psychology at Manchester Metropolitan University whose research includes a project about community resilience in Guatemala, warned against treating loneliness as an ‘all-or-nothing’ state.

“As a psychologist, I don’t think there are such things as ‘the lonely people’. There are people who, at some time during the day, might feel loneliness, and then other times during the day they might feel something else, like togetherness. It’s very possible to be lonely with lots of people around you, and that brings up the difference between loneliness and social exclusion. What are the factors which, during those 30 minutes when you weren’t lonely, made that?

Sometimes we focus so much on what makes this bad thing, loneliness. Something we did in Guatemala was try to focus on when things were good. Because things are very difficult living in Guatemala City when you’re working on the street. But when things are good, what makes that happen? It’s important to get away from homogenising people.”

Later, when talk turned to the groups of people most at risk of loneliness, photographer and Sense UK ambassador Ian Treherne brought a personal perspective to the debate by sharing his experience as someone who feels lonely as the result of a disability:

“Last year I was one of the subjects of a book by Nick Duerden called A Life Less Lonely. In this book are about 15 different types of people. There are so many different variations of loneliness, myself included. It could be a young person with an illness, an elderly chap who’s lost a wife, someone who’s got cancer and is no longer at work, and they now can’t work and are completely lost.

It’s purpose that drives people. If people have purpose, it keeps them active, involved, engaged. If they don’t have that purpose and they’re also isolated, it’s like a double whammy of being totally cut off. Purpose enables them to get out and distracts them from that isolation and loneliness.”

As the day progressed, the discussion shifted towards potential built environment interventions to address loneliness, with panellists debating how to improve day-to-day infrastructure – particularly transport options, housing and public realm – in ways that could imbue citizens with an increased sense of connection, ownership and belonging. Suggestions included rethinking traditional housing typologies to create more community-oriented neighbourhoods, restructuring the planning process to include more engagement of individual voices, and enhancing basic inclusive design principles.

The roundtable was a valuable exercise for exploring the breadth of people affected by loneliness and the potential for private and public spaces to promote meaningful forms of togetherness. The following section of this report examines how some of the themes above intersect across different sectors and locales. It also presents some design-led thinking around the subject from architects at Make.

Addressing loneliness is a complex effort that draws on expertise from many fields, from psychology and social science to public health and the third sector. The built environment industry is likewise cross-disciplinary, spanning architecture, urban design, construction, public policy, engineering, economics and more. A natural starting place for the Foundation’s research into urban loneliness was acknowledging the variety of professional spheres associated with this subject and including them in our discussion around it.

In 2019 we held a roundtable to examine the ways that loneliness affects people in urban areas and interrogate the role of the built environment in prompting and potentially relieving loneliness. We invited designers, policy advisers, academics and community organisers to offer both professional and personal perspectives on the issue.

Over the course of the event, the panel engaged in a series of discussions and workshops focused on identifying real-life instances of loneliness – how it comes about, who it affects, and what it’s like to experience this within an urban context. The panel’s expertise spanned a range of sectors, disciplines and demographics, which was especially useful in terms of considering the experiences of those with disabilities and other marginalising factors, as well as thinking internationally and across ethnic and class lines.

Some of the prominent lines of enquiry that surfaced included the difference between self-imposed and involuntary isolation; the role of technology as both a cause of and a remedy for loneliness; the benefits and limits of public space in fostering meaningful connections; the importance of public engagement and the inclusion of individual voices; the divisive nature of tribalism; and the forms of willpower, funding and organising – both public and private – needed to effect change.

An early line of conversation saw the panellists seek to define the loneliness by describing its antithesis. Initial suggestions included “happiness” and “connection,” although Andre Reid, founder of design practice KIONDO, pointed out that “connection isn’t necessarily the opposite of loneliness, but more or less the experience that’s desired. Loneliness is the inability to share one’s entire self with the surrounding world, and could be viewed as a ‘force’ which reminds us to foster genuine, empathetic connections with our environments.”