Birmingham case study

We have applied our decision framework to Birmingham to propose alternative ways to tackle the city’s housing shortage. All numbers below were current at the time of publication.

The city of Birmingham – the UK’s second largest city – has substantial problems with overcrowding, particularly in the suburbs to the east of the city centre, where there is a high immigrant population. It is also experiencing significant growth in employment and population, and has a shortage of available development land relative to the homes that need to be built.

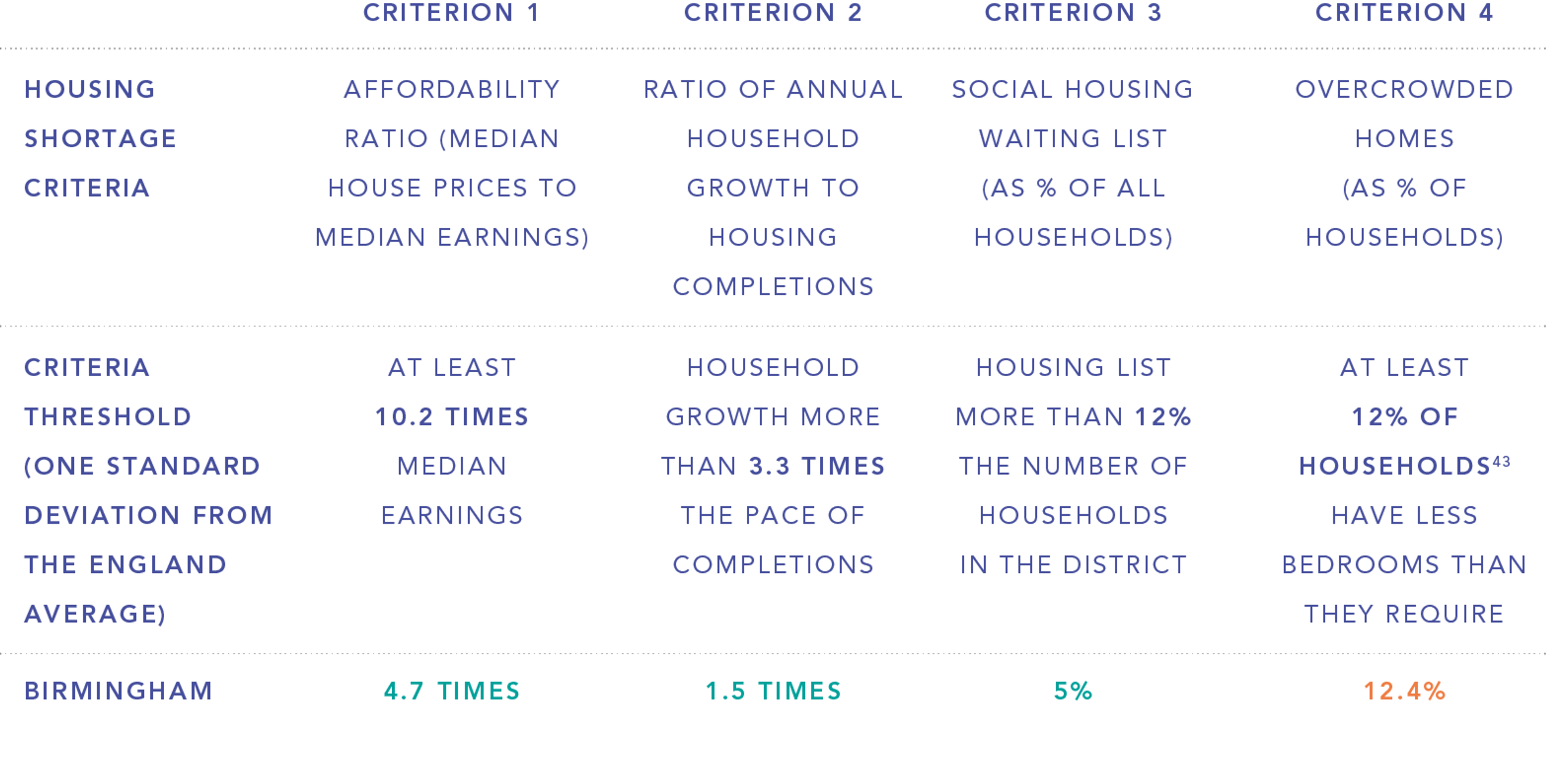

Birmingham has a housing shortage in terms of the quantity, quality and type of housing available. If past trends were to continue into the future, at least 4,100 homes would need to be built in Birmingham each year up to 2031. The high number of overcrowded homes within the city indicates there is a shortfall of housing of the right size in Birmingham (see below). This issue is most serious in the private rented sector, where 23.1% of households are living in overcrowded accommodation.

Overcrowding represents just one aspect of Birmingham’s housing problem. While the housing shortage criteria suggest that the number of homes completed has been on average sufficient to meet demand, on closer inspection large variations exists between local housing markets. For example, in the city centre strong demand exists for apartments and yet not enough dwellings of this type are being provided to meet the market’s need. There are also localised issues of affordability – for example, in Edgbaston where average prices are twice as high as the Birmingham average, restricting the ability of long-term residents to purchase homes in their neighbourhoods.

Development land has only been identified for up to 46,830 dwellings in Birmingham for the period 2014 to 2031. The Birmingham plan specifies the following minimum densities for new housing: 100 dwellings per ha within the City Centre, 50 dwellings per ha in areas well served by public transport, and 40 dwellings per ha elsewhere. Comparing supply to projected demand for new homes there is a shortfall of approximately 1,500 homes per year for the period up to 2031. For the whole year up to April 2014 (latest data from DCLG), just 1,010 homes were built in Birmingham – only a quarter of the homes that are needed. Just once over the past decade (in 2006) did Birmingham manage to meet its housebuilding targets.

The challenges presented in supplying sufficient housing within the city boundaries mean that Birmingham residents often move to surrounding districts to find appropriate housing. Birmingham has net out-migration equivalent to 0.5% of the population each year, more than the level of out-migration in Leeds (0.2%) but less than that of London and Manchester (0.7% of population). The vast majority (87%) of out-migrants stay in the wider West Midlands region.

The objective of the council is to meet as much of the housing need as possible within the city’s boundaries. A public consultation held in late 2012 put forward a range of options to deliver a sustainable urban extension of between 5,000 and 10,000 dwellings. The council considers that only Birmingham’s green belt has areas of land large enough to accommodate such an extension. This has led to a proposal to re-draw the green belt boundary by building an urban extension at Langley and Peddimore in Sutton Coldfield with space for 6,000 dwellings and 80 ha of employment land. This proposal has experienced significant opposition from local resident committees, which take the view that no development should take place and the council should instead focus on developing inner city sites and securing cooperation for more homes in the wider region.

The ongoing issue of overcrowding in Birmingham will likely get more serious as the city expands. To address the problem and to bring the high level of overcrowding down to the average in England (8.7% of households), Birmingham would need to build 10,900 homes between now and 2025 – including 1,800 social rented homes and 2,500 for the private rented sector.

The trend towards the concentration of employment in cities and large towns means that the most sustainable long-term solution to the housing shortage is to find ways to build more homes within cities. The alternative is to build homes further and further away from where people work, with the accompanying impact on the environment and rising cost of commuting. The biggest challenge will be to design homes within cities in a way that provides a desirable environment for families to live in the long term.

The FSF recommends (in order of priority) that:

- Building at higher densities within Birmingham should be preferred above all else.

- Building urban extensions should be applied only when all options of identifying appropriate brownfield sites within the city boundaries have been exhausted.

- Providing homes in other districts should only be considered as part of applying a more structured approach to planning for housing Birmingham residents who would migrate to these districts in any case.

Read more about this case study here.